Manga Vision: Cultural and Communicative Perspectives is an exciting exploration of manga (Japanese comics) from academic and artistic perspectives, edited by Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou and Cathy Sell, and published by Monash University Publishing.

The book is an enriched research volume, in that, in addition to scholarly articles, it contains a number of multimedia enhancements designed to supplement the reader’s experience many of which you will find here as online materials, including music and image files, teaching materials, and a bilingual terminology database.

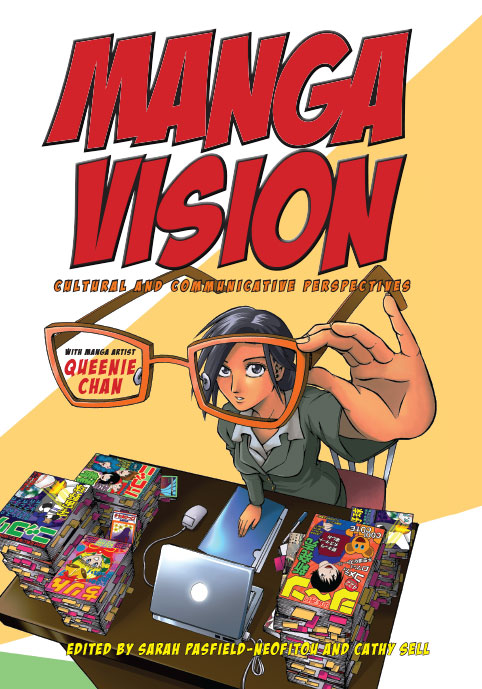

Manga Vision also features specially commissioned cover art and single-page manga prefacing each section by Australian manga artist Queenie Chan

Click on a chapter below to view the abstract and author biographies.

⭐ Online multimedia that complements the published volume, including additional supplementary material and high-resolution images, is accessbile by clicking on the categories above, or the relevant chapters below which are prefaced with a star icon.

Japanese comics, called “manga”, have a long history, with some scholars tracing their origins in Japanese cultural and aesthetic traditions dating back hundreds of years. More recently, the distinctive art style of manga has influenced animation, video games, film, music, and merchandising worldwide. As a key component of the modern media landscape, manga provide an important base for the study of cultural consumption and fan practices, including costume play or “cosplay”, conventions, fan fiction and art, including “dōjinshi”. Examined from both cultural and communicative perspectives, manga acts as an important lens through which to understand not only Japanese culture and the supposed essence of “Japaneseness” in the era of “Cool Japan”, but also notions and depictions of international relations, cross-cultural encounters, issues of orientalism, and aspects of global fandom and production.

This chapter examines the history of manga, locating comics in Japan, and on a global scale. It introduces the cultural and communicative perspectives, both visually and linguistically, that manga offers readers, via a meta-analysis of the literature in the emerging field of Manga Studies. The chapter further explores the potential that manga has to function as a tool for researchers to examine linguistic, aesthetic, and cultural environments.

Sarah PASFIELD-NEOFITOU

Monash University

Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou is a lecturer in Japanese Studies at Monash University. She holds a PhD in Japanese applied linguistics, has authored a number of articles in this area, and the book Online Communication in a Second Language (Multilingual Matters, 2012). She has previously worked with Cathy Sell on the translation of an art exhibition catalogue, and contributed a title on manga for the MWorld app.

Manga Vision features specially commissioned cover art and a single-page manga preface to each section by Australian manga artist Queenie Chan.

Queenie CHAN

Professional Manga Artist

Queenie Chan was born in 1980, and is an artist who specialises in OEL manga. In 2004, she began drawing a 3-volume mystery-horror series called The Dreaming for LA-based manga publisher TOKYOPOP. Since then, she has collaborated on several single-volume manga with best-selling author Dean Koontz, with the books reaching the New York Times best-seller list. After that, she worked on Small Shen, a prequel to Kylie Chan's best-selling White Tiger fantasy series, which was published in late 2012. Queenie's website is www.queeniechan.com

Click on the thumbnails of the single-page manga below to enlarge them. You can also view Queenie's artwork in high resolution by downloading the Open Access digital edition of the volume.

Manga © 2016 Queenie Chan.

The chapters in this section, authored by manga scholars and artists, explore manga as an expansive medium through which to express and develop personal identities and group cultures. The section begins with examinations of worldwide manga fandom, exploring both reader fan groups and individual appropriations of Japanese manga for personal uses, and in turn, the cultural ownership and expansion of manga culture internationally. The place of manga amongst other forms of popular culture, including anime, magazines, movies, and online media is a key theme of many of the papers in this section. Central to the chapters in section one is the issue of what constitutes manga, and who owns it – including the question of the definition or framing and ownership of particular manga genres such as yaoi.

Manga character designs are a key source of inspiration for cosplay (kosupure), a fan practice centering on the construction and wearing of character costumes. Driven by an affinity for the character or its source text, an admiration for the aesthetics of the character design, or the desire to create a costume that is valued by the cosplay community, cosplayers can spend considerable time, money and effort in recreating manga character designs in the form of wearable costumes. Drawing upon ethnographic fieldwork, this chapter will explore the processes of (re)creation of manga cosplays, charting the cosplayer’s transformation of an illustration into a costume. It will examine the particular ways cosplayers “read” manga during cosplay construction: as a source of creative inspiration, as “research” materials, and as a style guide for achieving accuracy in both costume and the performance of a character.

The chapter demonstrates how in the contexts of convention competitions and photo-shoots, the costumed cosplayer attempts to recreate the manga character through physical and/or verbal performance. In these contexts, cosplayers may draw more heavily upon the narrative of the manga as scenarios, poses and catch-phrases may be incorporated to create an “accurate” and entertaining performance of the character.

Claire LANGSFORD

University of Adelaide

Claire Langsford is a Visiting Fellow at the University of Adelaide’s Department of Anthropology and Development Studies. Drawing on a material culture approach, her Ph.D thesis explored the concept of transformation within the Australian cosplay community of practice, examining the transformations between textual and material, digital and physical, local and global.

Click on the images to enlarge them. Photographs © 2016 Claire Langsford.

In addition to fan practices like cosplay, some manga fans outside of Japan are interested in creating their own manga as a career path. In North America, the comics they create are called “Original English Language” (OEL) manga. These manga attempt to resemble Japanese manga aesthetically, by imitating the linework, panel layouts, manga-specific symbols, pictograms and onomatopoeia, as well as the use of monochrome and shading tools such as screentones, typical of Japanese manga. OEL artists use what they know as fans as guides for creating their own manga.

The exploding popularity of manga in North American quickly saw the appearance of local manga making and, riding on this wave of popularity, publishers were quick to commercialize OEL manga as another avenue for profit. Perhaps because of its hasty beginnings, OEL’s recent appearance in the arena of comics makes it difficult to determine what constitutes a work that can be deemed representative of the style and narrative within the abundant, yet multi-faceted examples of original manga or manga-style comics. This chapter proposes the possibility of identifying original characteristics that go beyond simulacrum and imitation of “Japaneseness”, and as an example, proposes professional OEL manga artist Svetlana Chmakova’s best-known work, Dramacon, as a case study for examining the creative and representative qualities of OEL manga.

Angela MORENO ACOSTA

Kyoto Seika University

Angela Moreno Acosta is a Venezuelan manga and anime influenced illustrator, who has a specialisation in story manga and has conducted research on OEL Manga. She holds a B.F.A in Illustration from Ringling School of Art and Design (2003), an M.A in Story Manga from Kyoto Seika University (2011) and a PhD in Art from Kyoto Seika University (2014).

Just as anime has its origins in manga, Japanese anime magazines developed from children’s publications and manga magazines such as Manga Shōnen which featured special content related to television animation. In the 1970s, anime “journalists” comprised hardcore fans, following a similar path to dōjinshi artists, turning professional by starting with fan-circle publications and proceeding to create professional outlets. As content began to deviate from that previously featured in manga magazines, publications such as Animage, Gekkan Out, Animec were born – commercial, yet retaining a distinct dōjin flavour common to original manga and anime video creations.

This chapter will plot the development of the anime magazine from manga magazines in Japan against the development of the anime industry, to give insight into the overall changes in the content of said magazines, and the ways in which fan/consumer and publication/production industry interaction was fostered and evolved through this dynamic transformation. It will consider the anime boom and decline of anime in manga magazines, manga-based anime, and anime’s turning point, and finally, anime journalism and the relationship between manga and anime today.

Renato RIVERA RUSCA

Meiji University

Renato Rivera Rusca, is a graduate of Japanese studies at Stirling University in Scotland and conducted his masters and doctoral research in Sociology on Japanese popular culture at Osaka University and Kyoto University. He is Assistant Professor in the Organization for International Collaboration at Meiji University, where he teaches Manga Culture and Animation Culture in the School of Global Japanese Studies and coordinates the Cool Japan Summer Program.

This chapter discusses the link between not only manga and anime, but other media such as film, via the specific example of the cinematic adaptation of the manga and anime series Death Note. The chapter focuses on Death Note’s representation of the pernicious social and moral effects of the Japanese media’s influence on attitudes towards the justice system. Three levels of discourse are identified: a) social commentary, focusing on calls for more punitive judicial action against criminals, b) psychological analysis, focused on ‘victimhood,’ and c) moral philosophy, focusing on ‘cosmic justice’ in an ostensibly post-religious society.

In examining these discourses, the chapter addresses the need to enrich and diversify moral discourse approaches to manga/anime (and their adaptations) to better reflect their status, functions and methodological possibilities as important media for social commentary in contemporary Japan.

Corey BELL

University of Melbourne

Corey Bell is a sessional teacher at the University of Melbourne’s Asia Institute. His primary research interests include the proselytic and pastoral uses of secular literary/popular culture genres in Zen Buddhism, and moral discourse in contemporary East Asian popular culture, particularly in Hong Kong and Japan.

Critical reading of manga can not only tell us about Japan in terms of how it is depicted, but explorations of fan communities’ perceptions of Japan based on these depictions provides valuable insight into the ways in which Japan is perceived globally. Most yaoi fans are unified by a common interest in Japan, and this chapter contributes to the relatively new debate regarding the diversity of yaoi fan practices, examining the relationships between yaoi and learning about Japan. To date, gender and sexuality have been a major focus of yaoi research, but online discussions do not always centre on fans’ identifications with sexuality. This paper proposes that Japanese culture is one key element underlying yaoi fans’ participation in the yaoi fan community.

Based on analysis of fan discussions and interviews, this chapter presents fan understandings and interpretations of Japan in five stages. Japan becomes known to yaoi fans through interpretation and discussions of yaoi manga content. As a result, fans filter what they know through stereotypes found in yaoi manga, their own beliefs, and the information given to them by others. The fandom’s interpretation is, on the whole, distinct from a reading of Japan as a complex identity or place without any single authentic narrative. Rather, Japan is found in a process of interaction and explanation amongst fans.

Simon TURNER

Chulalongkorn University

Simon Turner is an associate professor of Cultural Studies at Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. His principle research interest lies in the field of Queer Studies, Affect Theory, Japanese Cultural Studies, and New Media Studies. He is currently researching cross-cultural reception of Japanese yaoi manga amongst users of yaoi fan websites using a multidisciplinary approach as well as the queer and affective practices of fandom.

Although numerous studies have examined the discourses of masculinity and sexuality in homoerotic manga marketed towards young girls/women known as yaoi or Boys Love, there has been little attention paid to the genre of bara, marketed towards homosexual men, despite the fact that various studies of Japanese homosexualities have highlighted the important role bara play within Japanese media, and particularly gay magazines, which represent ‘gateways’ to knowledge about male homosexual desires in Japan.

This chapter examines how various stereotypes of gay subjectivity are discursively constructed within the bara published in Bádi, a Japanese gay magazine. Analysis suggests that bara appearing in Bádi can be divided into three thematic clusters: Slice-of-Life, Humorous, and Erotic. Each is argued to present different discourses of gay subjectivity. Furthermore, subjectivities were found to be constructed through both linguistic and stylistic means, and this chapter argues that language and physicality act as socially salient semiotics which index various tropes of stereotypical subjectivity.

Thomas BAUDINETTE

Monash University

Thomas Baudinette received his PhD in Japanese Studies from the School of Social Sciences, Monash University. His research focus on how engagement with media and space influences young Japanese gay men’s understandings of their gay desires and identities. Thomas has a strong interest in queer studies, critical race and gender theory, and the study of Japanese popular culture. He is currently preparing a monograph, based on his thesis, on the contemporary Japanese gay media landscape.

Manga has a unique aesthetic, a visual language of its own. Manga, and its sister medium, anime, have inspired artists from a variety of disciplines including sculpture and film. But how might a composer respond to anime? When the dominant visual aesthetic of manga is used to inform and inspire a different sensory art world, what is created and what is explored? This chapter draws upon the composition of a piece of piano music , Tides of Falling Leaves, which responds to material within the yaoi manga genre. It details the way manga informed this creative process and how the music acts as a way of remediating the visual gestures unique to manga.

As an example of practice-related research, the compositional process described in this chapter highlights a number of questions relating to inter-media relationships. Providing the theoretical framework for this research are the complimentary concepts of 'ekphrasis' and 'translation' – tools for examining works that straddle disparate media. Accompanying these is a move away from representational thought. When manga disconnected from an expected form of representation, its artistic vibrancy takes on a number of new roles, inviting a rethinking of the potential for intermedia dialogue, between languages and artists.

Paul SMITH

University of Western Sydney

Paul holds an honours degree in composition from the University of Western Sydney and is currently completing a Doctorate of Creative Arts exploring Japanese visual culture and music. He works as a casual lecturer/tutor at UWS and the University of New England and as a freelance singer in the greater Sydney area. His recent Kawaii Suite was featured on an album of contemporary piano music by Antonietta Lofreddo.

Click on music score images to enlarge them. Music score images and audio © 2016 Paul Smith.

In contrast with the first section, which focused on the visual and cultural elements of manga and related media, this section deals mainly with language. The chapters in section two, written by manga scholars and language education practitioners, examine linguistic expression and communication in manga, treating manga as a multi-modal medium through which to understand, learn and interact. The first part of this section includes examinations of how manga depicts language, both languages other than Japanese, and Japanese itself, while the second part considers how the linguistic content of manga may be utilised as a resource for teaching and research, in order to understand and further language learning and cultural engagement.

Nodame Cantabile depicts the story of Noda Megumi, portrayed as an eccentric, weak student, despite her special gift for music. She neither fits in the world of institutionalised music education nor follows socio-cultural norms in daily life. Although the main themes are Nodame’s development as a musician, and her relationships with others, especially love interest, Shin’ichi, there are three interesting episodes of language learning. First, Nodame has to pass a German examination. What can she, or Shin’ichi, as reluctant tutor, do in just one night? The second and third examples occur in Paris, where she is to study piano. After a failed attempt to learn everyday French expressions via a book, Nodame discovers a perfect method.

This chapter considers what insights Nodame’s language learning offers teachers and learners. The overall experience certainly reflects the gender and socio-economic differences between the two characters. Shin’ichi, with his privileged background, seems able - always and already – to speak and perform fluently. Nodame, rather, must learn, in accordance with the shōjo convention of finding one’s position (ibasho). Finally, we argue that the meta-learning and intertextuality of Nodame take us beyond stereotypes, even though the film/anime versions may not necessarily have the same effect.

Tomoko AOYAMA

University of Queensland

Tomoko Aoyama is an associate professor of Japanese language and literature at the University of Queensland. Her research focuses on parody, intertexutality, gender and humour in modern and contemporary Japanese literature. She is the author of Reading Food in Modern Japanese Literature (University of Hawaii Press, 2008) and the co-editor of Girl Reading Girl in Japan (Routledge, 2010) and Configurations of Family in Contemporary Japan (Routledge, 2015). She has also edited special issues of Japanese Studies (2003), Asian Studies Review (2006, 2008), and US-Japan Women’s Journal (2010) and co-translated Kanai Mieko's novels, Indian Summer and Oh, Tama!.

Belinda KENNETT

University of Queensland

Belinda Kennett is a lecturer in Japanese at the University of Queensland. Her research interests focus on language education and language teacher education, particularly in relation to Japanese as a Foreign Language (JFL) education and English language education in Japan. She is currently analysing various forms of language edutainment on Japanese television and on mobile devices and investigating the topic of swearing and bad language by Second Language Learners.

While numerous studies have noted extensive flexibility within written Japanese, the use of this potential in representations of non-native speakers’ (NNSs) Japanese has rarely been examined. Despite a significant increase in the number of foreigners achieving high levels of fluency and visibility, little data exists regarding how modern authors balance Japan’s tendency to demarcate foreign speech with the nation’s increasing diversification.

This chapter attempts to shed light on these issues by looking at some ways in which two manga authors use the medium’s flexible nature to portray foreigners’ speech through departure from orthographic norms. This appears to be a part of manga’s particular tendancy to use visual resources to portray conversation, given the medium’s lack of grammatical scaffolding. Like bolding or font, changes to script appear to be used to mark registers or tones with adjustments intended to elicit certain feelings or serve as guides for interpretation. Viewed in context, the handling of scripts can therefore provide a glimpse into the viewpoints of an author based on their cross-cultural experiences, as well as those they assume of their audience.

Wes ROBERTSON

Monash University

Wes Robertson is currently a PhD candidate in Monash University’s School of Languages, Literatures, Cultures and Linguistics, where he also tutors Japanese. His research is focused on the use of script to create meaning, specifically within Japanese writing. He received his bachelor’s degree from Macalester College, USA, in 2008, and completed an MA in applied Japanese linguistics at Monash in 2013.

Manga often present a challenge for non-native speakers (NNSs) of Japanese unaccustomed with reading from right-to-left, vertically. This chapter examines the manga reading behaviours of learners with different levels of Japanese language experience. One group was enrolled in an advanced Japanese language course in which they read manga, the other was enrolled in a Spanish language course. Some had studied Japanese, and some indicated they had read manga in English. The purpose of examining these groups was to gain an understanding of non-native readers’ initial knowledge state for reading Japanese manga, and the distance second language learners must travel in becoming more proficient readers of Japanese manga.

One important aspect of reading manga is to move from panel to panel or to sequence the panels right to left and top to bottom. We asked non-native readers to sequence panels in three conditions: 1) empty manga panels (koma); 2) koma with visuals (no text); and, 3) full manga, that is, koma with visuals and text present. This chapter compares and contrasts the two groups’ performance and documents learners’ strategies for sequencing manga according to the direction in which they sequenced panels and the continuity of how they enumerated panels.

James F. LEE

University of New South Wales

James F. Lee is Deputy Head of the School of Humanities and Languages. His main interest is in cognitive factors in instructed second language acquisition. His research interests include input processing, reading comprehension and the relationship between the two. He has published extensively on processing strategy training.

William S. ARMOUR

University of New South Wales

William S. Armour is an Honorary Senior Lecturer in the School of Humanities and Languages where he taught Japanese as an additional language for over two decades. His research interests include the history of Japanese popular culture in Australia and the relationship between the practices of Japanese language pedagogy and curriculum construction. From 2005 until 2013, he used manga as the medium for teaching the Japanese language.

Manga have long been a form of recreation but in recent years they have been used in many language classrooms around the world, especially for Japanese language learners. However, as manga is increasingly translated into other languages, it is now being used in the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classroom also.

In an elective language course at a private university in Japan, students studied manga in English and through critical thinking considered the different aspects within the manga, such as visual, linguistic and cultural elements, character development and also the story. Students were then given opportunities to compare and contrast Japanese manga and English language comics in order to identify the different elements as above and also to examine language. This chapter will discuss and show examples of how manga can be used not only to study Japanese, but how EFL students used manga as a tool to study English and also to investigate and understand popular culture in both Japan and abroad.

Lara PROMNITZ-HAYASHI

Juntendo University

Lara Promnitz-Hayashi is a lecturer at Juntendo University in Tokyo, Japan. She has completed an MA in applied linguistics and an MEd in TESOL. She is currently completing a doctorate of education at the University of Southern Queensland. Her research interests include language teaching pedagogy and methodology, bilingualism, Australian English, CALL, code-switching and popular culture.

Available for download as a portable document format (pdf) file.

EFL Worksheet © 2016 Lara Promnitz-Hayashi.

The ‘naturalness’ of manga dialogues and variety of language presented in manga has attracted much attention in reent years, not only from educators, but also linguistic researcers. Manga dialogues include pragmatic elements such as relationships, context and narrative (e.g. Chinami, 2003, 2007; Takahashi, 2009), which make them an ideal source for linguistic data. Linguistic research in the past decade has emphasized the use of ‘authentic’ data. This has functioned to increase the understanding of communication in Japanese. However, such research has generally focused on polite encounters, and not much is known about ‘impolite’ language in situations like fights or arguments. The lack of studies in this area might be related to the difficulty in obtaining data on ‘impolite’ encounters.

Manga dialogues provide an alternative to authentic exchanges in the case of situations for which recordings are not possible or are difficult to obtain. They depict a variety of interactions where we know the characters’ relationships and additional factors that affect their language. This chapter explores Japanese linguistic impoliteness using manga as data, aiming to discern the type of strategies used and the situations in which impoliteness occurs.

Lidia TANAKA

La Trobe University

Lidia Tanaka has taught in the Japanese Program of La Trobe University for more than 20 years and is currently an Honorary Associate in the Languages and Linguistics Department at the same institution. She is the author of Gender, Language and Culture (John Benjamins 2004) on the factors of age and gender in Japanese television interviews. Her research interests are in Japanese communicative interaction, gender and language, ‘institutional’ language, and ‘impoliteness’ in the media.

Having explored the use of language in manga to depict insiders and outsiders, and the power of language in manga, this chapter turns to examine manga-based narratives relating to Japan and Korea. Relations between Korea and Japan have an unsettled history, leading to a 'love-hate' relationship. Events often attributed to the rise of 'anti-Korea' and 'anti-Japan' sentiments in Japan and South Korea range from Japanese invasions of the Korean peninsula in the 16th century, the 35 years of occupation in the 20th century, and post-wrar events such as Japan's alleged 'lack of historical recognition', to South Korean claims to Japanese intellectual property (Lee Y, 1998), and the ongoing 'Takeshima/Dokdo Island problem'.

In the 21st century, a boom in Korean pop culture in Japan has provoked anti-Korean sentiment in some circles, as illustrated by the controversial manga 'Hate Korean Wave' (Kenkanryū), by Yamano Sharin. The comic led to a response from South Korean comic artist Byeong-seol Yang, who produced 'Hate Japanese Wave' (Hyeomillyu). These comics, their use as propaganda, and their effect on relations between the countries have been widely discussed in Japan and, to some extent, Korea. However, scholars without knowledge of the source language cannot fully participate in such a debate, hence the need for impartial translations. Drawing upon the process of translating both comics into English, this chapter discusses strategies for dealing with controversial material, in the visual context of manga.

Adam Antoni ZULAWNIK

Monash University

Adam Antoni Zulawnik graduated from the University of Auckland, New Zealand, where he completed a BA in Japanese and Korean Studies. In 2012, Adam completed combined Honours (First Class) in Japanese and Korean Studies at Monash University, Australia. Adam is currently a PhD (translation) candidate at Monash University where he is continuing research focusing on risk and ethics in the translation of ‘controversial’ texts.

A major issue in the translation of manga is the matter of onomatopoeia and mimesis, due to aesthetic, textual and linguistic complexities. These ‘sound effects’ are used to great effect in order to convey an aural environment visually, and are more often than not part of the artwork aestheticly, in the way that the page is constructed, and the fact that they are usually hand drawn. Stylized onomatopoeia and mimesis illustrate well the interrelated nature of images and text in the medium, as, in a sense, they are both image and text. The disparity in the sheer number of onomatopoeic and mimetic expressions in Japanese and English makes the translation of these words difficult. Often, equivalent vocabulary in English simply does not exist, and so translators have developed various strategies by which to fill the void.

This chapter examines the challenges of manga translation by introducing the aesthetic difficulties created by the script-artwork integration, in tandem with page layout complexities owing to the difference between textual conventions. It concludes by analysisng strategies employed by manga translators to deal with the linguistic disparity of onomatopoeia and mimesis between the source and target languages, and typographic strategies to address aesthetic concerns.

Cathy SELL

Monash University

Cathy Sell holds a PhD from Monash University where she currently teaches translation and Japanese. She is a NAATI accredited professional translator specialising in fine arts and popular culture. Her primary research interests relate to multimodal communication, including translation and semiotics in Japanese art museums, manga as an intercultural medium, and sign language teaching and learning.

Sarah PASFIELD-NEOFITOU

Monash University

Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou is a lecturer in Japanese Studies at Monash University. She holds a PhD in Japanese applied linguistics, has authored a number of articles in this area, and the book Online Communication in a Second Language (Multilingual Matters, 2012). She has previously worked with Cathy Sell on the translation of an art exhibition catalogue, and contributed a title on manga for the MWorld app.

The Manga Studies SFX Glossary is a collection of Japanese onomatopoeia and their corresponding English translations compiled from Japanese and English volumes of professionally published manga.

Visit glossary pageDesigned for use in teaching Japanese as a Foreign Language at beginner to advanced levels, these resources can be used in the classroom to introduce students to the rich variety of Japanese onomatopoeia.

Onomatopoeia and Mimesis Translation Worksheet

This single-page worksheet is designed for classroom use teaching translation from Japanese to English. It can be used to teach strategies for dealing with onomatopoeia and mimesis in translation, as well as giving students an introduction to the breadth of onomatopoeia and mimesis in Japanese. It implements the practical use of manga in the classroom.

Available for download as a Portable Document Format (pdf) file, with or without furigana.

Manga and manga culture at large offer the opportunity for an enhanced understanding of cultural and communicative expression through academic study and discourse. In particular, as primary source material, manga affords a textual-visual medium for the depiction, reception, and appraisal of both a linguistic and sensory world that is otherwise difficult to view. Examination of related media such as anime and games, as well as the interaction of the audience/readership as both consumers and creators of manga culture, opens up endless research possibilities, and it is this contextual cultural system that is a particular strength for manga as a research tool.

This concluding chapter discusses the enhancements that manga and its culture make to our understanding of cultural and communicative expression, and reflects upon the views presented throughout both sections of the book, including areas of cross-over, and directions for future research.

Cathy SELL

Monash University

Cathy Sell holds a PhD from Monash University where she currently teaches translation and Japanese. She is a NAATI accredited professional translator specialising in fine arts and popular culture. Her primary research interests relate to multimodal communication, including translation and semiotics in Japanese art museums, manga as an intercultural medium, and sign language teaching and learning.

Artland Newspaper: Dai-4-kai sutajio shinbun: Aatorando no maki (Artland Newspaper: Studio Newspaper, Issue 4: The Artland issue), (1984, October), The Motion Comic, 9, 203-211, Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten

Azuma, Hiroki. (2012). Database animals In Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe & Izumi Tsuji (Eds.), Fandom unbound: Otaku culture in a connected world New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Bernabe, Marc. (2004). Japanese in MangaLand. Tokyo: Japan Publications.

Berndt, Jaqueline and Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina. (Eds.) (2013). Manga’s Cultural Crossroads. New York: Routledge.

Boilet, Frédéric. (2010). Nūberu manga (Nouvelle Manga). Retrieved from http://www.boilet.net/am/dernieres_nouvelles.html

Bouissou, Jean-Marie, Pellitteri, Marco, Dolle-Weinkauff, Bernd, & Beldi, Ariane. (2010). Manga in Europe: A short study of market and fandom. In Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.), Manga: an anthology of global and cultural perspectives (pp. 253-266). New York; London: Continuum.

Brenner, Robin E. & Wildsmith, Snow. (2011). Love through a different lens: Japanese homoerotic manga through the eyes of American gay, lesian, bisexual, transgender and other sexualities readers. In Timothy Perper & Martha Cornog (Eds.), Mangatopia: Essays on Manga and Anime in the Modern World (pp. 89-118). Santa Barbara; Denver; Oxford: Libraries Unlimited.

Brienza, Casey. E. (2009). Books, not comics: publishing fields, globalization, and Japanese manga in the United States. Publishing Research Quarterly, 25(2), 101-117.

Brown, Steven T. (Ed.). (2006). Cinema anime: Critical engagements with Japanese animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cohn, Neil. (2010). Japanese Visual Language: The Structure of Manga. In Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.), Manga: an anthology of global and cultural perspectives (pp. 187-203). New York; London: Continuum.

Cohn, Neil. (2011). A Different Kind of Cultural Frame: An Analysis of Panels in American Comics and Japanese Manga. Image [&] Narrative, 12 (1). Retrieved from http://www.imageandnarrative.be/index.php/imagenarrative/article/viewFile/128/99

Condry, Ian. (2013). The Soul of Anime: Collaborative Creativity and Japan’s Media Success Story. Durham: Duke University Press.

Cubbison, Laurie. (2005). Anime fans, DVDs, and the authentic text. The velvet light trap(56), 45-57.

Davidson, Danica. (2012, January 26). Manga Grows in the Heart of Europe. CNN. Retrieved from http://geekout.blogs.cnn.com/2012/01/26/manga-in-the-heart-of-europe/

Drazen, Patrick. (2011). Reading right to left: The surprisingly broad appeal of manga and anime; or ‘Wait a minute’. In Timothy Perper & Martha Cornog (Eds.), Mangatopia: Essays on Manga and Anime in the Modern World (pp. 135-150). Santa Barbara; Denver; Oxford Libraries Unlimited.

Gakken Group Official Homepage. Retrieved from http://hon.gakken.jp/child/study/comic/

Gan, Sheuo Hui. (2011). Manga in Malaysia: An Approach to Its Current Hybridity through the Career of the Shōjo Mangaka Kaoru. International Journal of Comic Art, 3(2), 164-178.

Goldberg, Wendy. (2010). The manga phenomenon in America. In Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.), Manga: an anthology of global and cultural perspectives (pp. 281-296). New York; London: Continuum.

Goodwin, Charles. (1994). Professional vision American Anthropologist, 96(3), 606 - 633.

Goodwin, Charles. (1997). The blackness of black: colour categories as situated practice. In Lauren. B. Resnick, Roger Säljö, Clothilde Pontecorvo & Barbara Burge (Eds.), Discourse, tools and reasoning: Essays on situated cognition (pp. 111-140). Berlin; Heidelberg; New York Springer.

Gowland, Geoffrey. (2009). Learning to see value: Exchange and the politics of vision in a Chinese craft. Ethnos: Journal of anthropology 74(2), 229-250.

Grasseni, Cristina. (Ed.) (2007). Skilled visions: Between apprenticeship and standards. New York: Berghahn Books.

Gravett, Paul. (2004). Manga: Sixty Years of Japanese Comics. London: Laurence King Publishing.

Hasebe, Daiki. (Producer/Editor), Ito, Hideaki. (2012): Uchū Senkan Yamato TV BD-Box Sutandaado-ban Fairu (Space Cruiser Yamato TV BD Box Standard Edition File), Tokyo: Gin’ei-sha/Bandai Visual

Hills, Matt. (2002). Fan cultures. London; New York: Routledge.

Hirose, Kazuyoshi. (1977, October), Animeeshon waarudo paato 1: Dai-1-kai dokusha ga erabu terebi anime besuto 10 happyō!! (Animation World, Part 1: We reveal the best 10 TV anime as chosen by readers!!), Manga Shōnen, issue 14, 283-285, Tokyo: Asahi Sonorama

Ima, anime e no michi: Anime gyōkai shūshoku jōhō (Now, the path to anime: anime employment information), Break Time, (1984 November), issue 2,17-24, Tokyo: Break Time Editorial

Ito, Kinko. (2003). The World of Japanese Ladies’ Comics: From romantic fantasy to lustful perversion. The Journal of Popular Culture, 36, 68-85.

Ito, Kinko. (2005). A History of Manga in the Context of Japanese Culture and Society. The Journal of Popular Culture, 38, 456-475.

Ito, Mizuko. (2010). Mobilizing the imagination in everyday play: The case of Japanese media mixes. In Stefan Sonvilla-Weiss (Ed.), Mashup culturres (pp. 79-97). Wien, Austria; New York: Springer.

Ito, Yu, Tanigawa, Ryuichi, Murata, Mariko & Yamanaka, Chie. (2013a). Visitor survey at the Kyoto International Manga Museum: Considering Museums and Popular Culture (Cathy Sell, Trans.). In Ryuichi Tanigawa (Ed.), Cias Discussion Paper No.28: Manga Comics Museums in Japan: Cultural Sharing and Local Communities. (pp.15-27) Kyoto: Center for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University.

Ito, Yu, Tanigawa, Ryuichi, Murata, Mariko & Yamanaka, Chie. (2013b). Visitor Survey at the Hiroshima City Manga Museum: What it Means to Deal with Manga in Libraries. (Cathy Sell, Trans.). In Ryuichi Tanigawa (Ed.), Cias Discussion Paper No.28: Manga Comics Museums in Japan: Cultural Sharing and Local Communities. (pp. 43-53) Kyoto: Center for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University.

Ito, Yu, Tanigawa, Ryuichi, Murata, Mariko & Yamanaka, Chie. (2013b). Visitor Survey at the Osamu Tezuka Manga Museum: Do Manga Museums Really Promote Regional Development? (Cathy Sell, Trans.). In Ryuichi Tanigawa (Ed.), Cias Discussion Paper No.28: Manga Comics Museums in Japan: Cultural Sharing and Local Communities. (pp. 29-41) Kyoto: Center for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University.

Iwabuchi, Koichi. (2002). Recentering globalization: Popular culture and Japanese transnationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

Iwashita, Hosei. (2011). Shōjo manga shōji (A Brief History of Shōjo Manga) (Jessica Bauwens-Sugimoto & Cathy Sell, Trans.). In Keiko Takemiya (Ed.), Shōjo manga no sekai (The World of Girls’ Comics) (pp. 60-61). Kyoto: Kyoto Seika International Manga Research Centre, Kyoto International Manga Museum.

Jenkins, Henry. (1992). Textual poachers: Television fans and participatory culture. New York: Routledge.

Jenkins, Henry. (2006): Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press

JPMA. (2013). Japan Magazine Publishers Association. Retrieved from http://www.j-magazine.or.jp/data_002/c4.html#001

Jüngst, Heike. (2007). Manga in Germany - From Translation to Simulacrum. Perspectives, 14(4), 248-259.

Jüngst, Heike. (2008). Translating Manga. In Federico Zanettin (Ed.), Comics in Translation (pp. 50-78). Manchester, UK: St. Jerome.

Kelly, William W. (Ed.). (2004). Fanning the flames: Fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan Albany: State University of New York Press.

Kelts, Roland. (2006): Japanamerica: How Japanese Pop Culture Has Invaded the U.S. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Kinsella, Sharon. (1998). Japanese subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and the amateur manga movement Journal of Japanese Studies 24(2), 289-316.

Komaki, Masanobu. (2009): Animec no koro (My Days at Animec), Tokyo: NTT Publishing

Lamarre, Thomas. (2009): The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Lammers, Wayne P. (2004). Japanese the Manga Way: An Illustrated Guide to Grammar and Structure. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press.

Lave, Jean & Wenger, Etienne. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, Jean. (1996). Teaching, as Learning, in Practice. Mind, Culture and Activity, 3(3), 149-164.

Lee, William. (2000). From Sazae-san to Crayon Shin-Chan. In Timothy J. Craig (Ed.), Japan Pop!: Inside the World of Japanese Popular Culture (pp. 186-203). Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Lunning, Frenchy. (2011). Cosplay, drag, and the performance of abjection. In Timothy Perper & Martha Cornog (Eds.), Mangatopia: essays on manga and anime in the modern world (pp. 71- 88). Santa Barbara; Denver; Oxford: Libraries Unlimited.

Mandarake: Shiryou-sei Dōjinshi Hakurankai (Data Resource Dojinshi Exposition). Retrieved from http://www.mandarake.co.jp/information/event/siryosei_expo/report.html

Marcus, George. E. (1998). Ethnography in/of the world system: the emergence of multi-sited ethnography. In George. E.Marcus (Ed.), Ethnography through thick and thin (pp. 79-104). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Matsui, Takeshi. (2009). The Diffusion of Foreign Cultural Products: The Case Analysis of Japanese Comics (Manga) Market in the US. Princeton University Center for Arts and Cultural Studies Working Paper Series, 37, Spring 2009. Retrieved from http://www.princeton.edu/~artspol/workpap/WP37-Matsui.pdf

McCloud, Scott. (1994). Understanding comics: the invisible art. New York: HarperCollins.

McCloud, Scott. (2011). Making comics. New York: HarperCollins.

Mcgray, Douglas. (2002, May 1). Japan’s Gross National Cool. Foreign Policy, pp. 44-54.

Media Geijutsu Karento Kontentsu (Media Arts Current Contents). Retrieved from www.mediag.jp/news

Nakazawa, Jun. (2002). Manga dokkai katei no bunseki (Analysis of Manga (comic) reading processes. Manga Kenkyū (Manga Research), 2, 39-49.

Nakazawa, Jun. (2004). Manga dokkairyoku no kitei’in toshite no manga no yomi riterashii (Manga (comic) literacy skills as determinants factors of manga story comprehension). Manga Kenkyū (Manga Research), 5, 7-25.

Nakazawa, Jun. (2005). Manga no koma no yomi riterashii no hattatsu (The development of manga panel reading literacy). Manga Kenkyū (Manga Research), 7, 6-21.

Napier, Susan J. (2001). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing contemporary Japanese animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Norris, Craig, & Bainbridge, Jason. (2009). Selling otaku?: Mapping the relationship between industry and fandom in the Australian cosplay scene. Intersections: Gender and sexuality in the Pacific (20).

Oguro, Yūichiro. (2008), Anime-sama 365-nichi, dai-3-kai: “Terebi Anime no Sekai” (Mr. Anime’s 365 Days, No. 3: “The World of TV Anime”). Web Anime Style. Retrieved from http://www.style.fm/as/05_column/365/365_003.shtml

Okabe, Daisuke & Ishida, Kimi. (2012). Making fujoshi identity visible and invisible. In Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe & Izumi Tsuji (Eds.), Fandom unbound: Otaku culture in a connected world (pp. 207-224). New Haven; London Yale University Press.

Okabe, Daisuke. (2012). Cosplay, learning and cultural practice. In Mizuko Ito, Daisuke Okabe & Izumi Tsuji (Eds.), Fandom unbound: Otaku culture in a connected world (pp. 225-248). New Haven; London Yale University Press.

Pasfield-Neofitou, Sarah. (2013). “Kūru Japan”: Intaanetto, media to ibunka komyunikeeshon (Cool Japan: The internet, media, and intercultural communication). Gurōbaru-ka to gaikai ni okeru nihongo kyōiku seminaa (Seminar on Globalization and Overseas Japanese Language Education). Chiba University, Japan.

Petersen, Robert. S. (2009). The acoustics of manga. In Jeet Heer & Kent Worcester (Eds.) A Comics Studies Reader (pp. 163-171) Jackson: Univ. Press of Mississippi.

Schodt, Frederik L. (1986). Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. Tokyo: Kodansha.

Schodt, Frederik L. (1991). Sex and Violence in Manga. Mangajin, 10, 9.

Sell, Cathy. (2011). Manga translation and interculture. Mechademia: User Enhanced, 6, 93-108.

Sell, Cathy. (2012) A Brief History of the JSC Manga Library. In Cathy Sell, Sarah Pasfield-Neofitou & Jeremy Breaden (Eds.), Manga Studies: A symposium celebrating 10 years of the JSC Manga Library at Monash (pp. 3-4). Melbourne: Monash University.

Shiina, Yukari (2012) “Manga sutairu nōsu amerika-ten - Kore mo manga? Beikoku de katsuyaku suru mangaka-tachi” minibukku. (Manga Style North America - Is this manga too? Manga artists active in North America Minibook) (Jessica Bauwens-Sugimoto, Trans.) Kyoto: Kyoto International Manga Museum.

Shove, Elizabeth, Pantzar, Mika, & Watson, Matt. (2012). The dynamics of social practice: Everyday life and how it changes. London: Sage.

Simmons, Vaughan. (Ed.) (1988-1998). Mangajin. Marietta: Mangajin Inc.

Sōryoku tokushū: SF anime to wa nanika?: SF anime ga mitai! (Collaborative special feature – What is SF anime?: We want to see SF anime!) , Animec vol. 20, 13-43 (1981, October), Tokyo: Rapport.

Sunaoshi, Yukako. (2006). Who reads comics? Manga readership among first-generation Asian immigrants in New Zealand. In Matthew Allen & Rumi Sakamoto (Eds.), Popular culture, globalization and Japan (pp. 94-114). London; New York: Routledge.

Syed, Saira. (2011, August 18). Comic Giants Battle for Readers. BBC News. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-14526451

Tanigawa, Ryuichi. (2013). Preface. In Ryuichi Tanigawa (Ed.), Cias Discussion Paper No.28: Manga Comics Museums in Japan: Cultural Sharing and Local Communities. (pp. 29-41) Kyoto: Center for Integrated Area Studies, Kyoto University.

The Japan Foundation (2011). Present Condition of Overseas Japanese-Language Education: Survey Report on Japanese-Language Education Abroad 2009. Tokyo: The Japan Foundation.

Thorn, Matt. (2011, April 11). The Tokyopop Effect. In Matt Thorn’s Blog. Retrieved August 26, 2013 from http://matt-thorn.com/wordpress/?p=495

Toku, Masami. (Ed.) (2005). Shojo Manga: Girl Power! Chico: Flume Press/California State University Press.

Tokyopop to Move Away from OEL and World Manga Labels (2006, May 5). Anime News Network. Retrieved August 26, 2013 from http://www.animenewsnetwork.com/news/2006-05-05/tokyopop-to-move-away-from-oel-and-world-manga-labels

Toshokan Mondai Kenkyūkai (1999). Tokushū: Toshokan de manga o teikyō suru ni wa. (Special Feature: Offering manga in libraries). Minna no toshokan (Everyone’s Library), 269.

Tsuji, Sōichi. (2012, October): Makurosu tanjō 30 shūnen kinen taidan: Kawamori Shōji x Mikimoto Haruhiko (Macross 30th Anniversary Celebration Discussion: Shoji Kawamori and Haruhiko Mikimoto), Gekkan Newtype Ace, 13, 388-395, Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten

Wong, Wendy Siuyi. (2006). Globalizing manga: from Japan to Hong Kong and beyond. Mechademia: Emerging Worlds of Anime and Manga, 1, 23-45.

Wong, Wendy Siuyi. (2010). Globalizing manga: From Japan to Hong Kong and beyond. In Toni Johnson-Woods (Ed.), Manga: an anthology of global and cultural perspectives (pp. 332-350). New York; London: Continuum.

Yabu’s Run (1977, September), Out, issue 5, 131-132, Tokyo: Minori Shobou

Z Gandamu waarudo, mekanikaru manyuaru (Zeta Gundam World Mechanical Manual), Animec (1986, January), 54-63, Tokyo: Rapport